What are the symptoms of measles – and what should you do if you think your child is infected? | uk news

A “rapidly spreading” measles outbreak in north London has infected more than 60 children, with nearly a dozen requiring hospital treatment.

The Sunday Times has reported that of the 60 suspected cases in Enfield, 34 have so far been confirmed by the UK Health Protection Agency between 1 January and 9 February.

According to a message posted by NHS Ordnance Unity Center for Health GP surgery, has become infected Confirmed in at least seven schools – “And it’s spreading.”

The surgery said none of the infected children were fully immunised, leading to fresh calls for parents to make sure their children are vaccinated.

so what are its symptoms, measles? What should you do if you think your child has the disease – and why are some people hesitant to get vaccinated?

What are the symptoms of measles?

The first symptoms of measles include:

• a high temperature

• runny or blocked nose

• sneezing

• Cough

• Red, painful or watery eyes

Cold-like symptoms are followed a few days by a rash, which starts on the face and behind the ears before spreading.

The spots are usually raised and may coalesce to form blotchy patches that usually do not itch.

Some people may also have small spots in the mouth.

What should you do if you think your child has measles?

If you think your child has measles, seek a GP appointment immediately or call 111.

If your child has been vaccinated, there is a very low chance that they will get measles.

You should not go to the doctor without calling, because measles is very contagious.

If your child has been diagnosed with measles by a doctor, make sure they avoid close contact with children and anyone who is pregnant or has a weakened immune system.

When should you keep your child away from school?

If your child has measles, they should stay away from school or nursery for at least four days after the rash appears.

Your child’s school or local health protection team will let you know if your child has been exposed to someone who has measles and tell you what you need to do.

People who are more vulnerable to infection, for example unvaccinated siblings of a child with measles, may be asked to stay away from school for 21 days.

What are the possible complications of measles?

If measles spreads to the lungs or brain, it can cause serious problems and, in rare cases, even death. About one in 5,000 people infected with measles is likely to die.

last year, A child died in Liverpool After becoming ill with measles and other health problems.

About 1 in 5 people with measles will need hospital treatment and 1 in 15 will develop serious complications.

Measles can cause deafness, seizures, pneumonia, meningitis, blindness, and brain damage.

People at higher risk of complications include infants and young children, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.

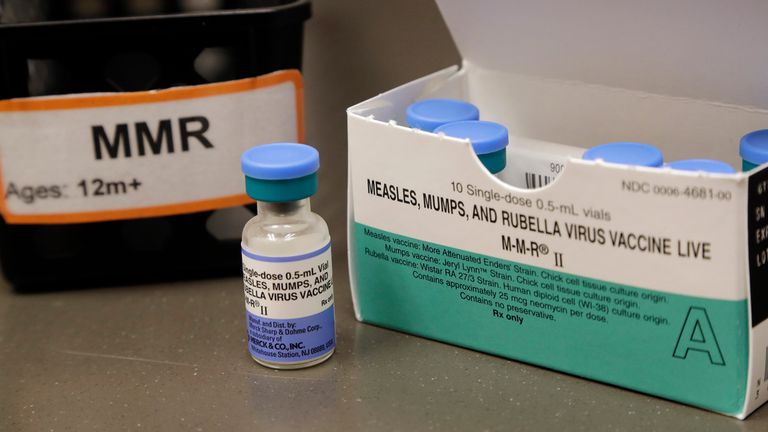

What is the MMR jab?

Measles vaccination in the MMR jab has been linked with protection against mumps and rubella. It is considered safe and highly effective.

The MMR vaccine was introduced in the UK in 1988 and the measles vaccine has been available since 1968.

There were between 160,000 and 800,000 cases per year in England and Wales, and about 100 people per year died from acute measles.

But since the vaccine was introduced in 1968, it is estimated that 20 million cases and 4,500 deaths have been prevented.

The MMR vaccine is given in two doses, which provide lifelong protection. The first dose is usually given to children at one year of age, with the second dose given at three years and four months.

If any doses are missed, you can still ask your doctor for the vaccine.

Falling vaccination rates are leading to an increase in cases.

Falling vaccination rates have sparked fears of a wider outbreak of the virus, the World Health Organization (WHO) has warned Britain. Lost its measles elimination status last month.

From 2021 to 2023, the country was believed to have “eliminated” the disease, but global health officials say measles transmission re-established in Britain in 2024.

Vaccination coverage has declined in recent years, with measles infections in the UK rising to 3,681 in 2024.

The latest figures from England show that in 2024-25, only 83.7% of five-year-olds had received both doses of the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine, down from 83.9% year-on-year.

this was the lowest level since 2009-10 And this is well below the 95% recommended by WHO to achieve herd immunity.

When and why did people stop vaccination?

In 1998, a study by British doctor Andrew Wakefield was published in The Lancet linking the MMR vaccine to autism.

The study was discredited, but not before the study received global media coverage, leading to a mass hysteria over the safety of the vaccine.

MMR vaccination in the UK fell by about 80% nationally in the late 1990s and early 2000s and took several years to recover.

In 2006, measles transmission became re-established in the UK, and in 2007, measles cases exceeded 1,000 for the first time in 10 years.

The Lancet retracted Wakefield’s study in 2010 and he was removed from the UK medical register.

Why are vaccination numbers still low?

Helen Bedford, professor of children’s health at the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute, told Sky News that a number of things could stop parents from vaccinating their children.

“This is mainly due to lack of access,” Professor Bedford said.

“People may not know when the vaccines are coming or how to make an appointment, and then actually make the appointment.

“For some parents who are poverty-stricken, paying bus fare to take their child to a GP surgery may be a step too far, even if they understand that vaccination is very important.”

Professor Bedford said that since the Covid pandemic, more parents are asking questions about vaccination, which may lead them to search the internet for answers.

“We want parents to ask questions but unfortunately due to a shortage of staff and health visitors, they don’t always get answers or even the opportunity to discuss them,” she said.

“That’s when they turn to other sources of information, like social media or the Internet, where we know there’s a lot of misinformation.”

Fears of a link to autism persist despite being proven false, and misinformation on social media has increased vaccine hesitancy.